- The Common Source for George North and Shakespeare on the Kingdom of the Bees.

- More on the Common Source for George North and Shakespeare on the Kingdom of the Bees.

McCarthy followed with a table of comparison of North's and Shakespeare's texts from his 2018 edition of North's text. I show that each example is taken from 1st century Rome by following each example with the corresponding English translation from the Loeb editions of Pliny's Natural History1 and/or Virgil's Georgics2. The correspondence shows that even 400+ years apart, the English translations that correspond to the Latin original show an unmistakable close relationship to both Tudor authors.

Together with this comparison, I provide key terms from the original Latin text in brackets. There are not many. But they should be simple to look up and they are chosen because they make particularly clear the precise match between the Latin and all of the English texts. Also, the Loeb editions can be downloaded for free from the Internet Archive in order to read the entire text in both languages.

|

...a single male which in each swarm is called the king; … He is surrounded by certain retainers and lictors as the constant guardians of his authority. [Pliny, 465] |

Here follows not only vocabulary but a very specific grammatical match using “some” and “other” precisely as in the Latin of the Georgics.

...a guard is posted at the gates ….they send scouts [speculatores] to further pastures. [Pliny, 445] |

They alone have children in common, hold the dwellings of their city jointly, and pass their life under the majesty of law. They alone know a fatherland and fixed home, and in summer, mindful of the winter to come, spend toilsome days and garner their gains into a common store. For some [aliae] watch over the gathering of food, and under fixed covenant labour in the fields; some [aliae], within the confines of their homes, lay down the narcissus' tears and gluey gum from tree-bark as the first foundation of the comb, then hang aloft clinging wax; others [aliae] lead out the full-grown young, the nation's hope; others [aliae] pack purest honey, and swell the cells with liquid nectar. To some [aliae] it has fallen by lot to be sentries at the gates, and in turn they watch the rains and clouds of heaven, or take the loads of incomers, or in martial array drive the drones, a lazy herd [ignavum fucos pecus], from the folds. [Georgics, 207, 209] |

It is clear from the two author's texts that North likely had the Pliny and Virgil texts beside him as he wrote. Shakespeare is much looser in his rendition and seems to be writing from memory of his originals.

|

To some it has fallen by lot to be sentries [custodia] at the gates, and in turn they watch the rains and clouds of heaven, or take the loads of incomers [aut onera accipiunt venientum],... [Georgics, 207] |

In the following, Shakespeare even matches the Loeb translation precisely. Both mention Virgil's tent-royal / royal tent, their exact translation of Virgil's praetoria.

|

Round their king [circa regem], and even by his royal tent [praetoria],... [Georgics, 201] |

|

They build large and splendid separate palaces [amplas, magnificas, separatas, tuberculo eminentes] for those who are to be their rulers... [Pliny, 451] |

The two obvious clues that one is reading a redaction or translation of Pliny and/or Virgil (or Aristotle, from whom they took more than a little of their information) are: 1) the hives are said to have a king rather than a queen; and, 2) a moral is drawn upon drones who are said to seek to devour the honey without having worked for it.

We've seen the king. Now the drones.

|

...drive the drones [fucos], a lazy [ignavum] herd [pecus], from the folds. [Georgics, 207, 209] |

|

When the honey has begun to ripen, the bees drive the drones away, and falling on them many to one kill them. [Pliny, 451]. |

The moral of the lazy drone was perhaps the most common in Tudor England.

The portions of Pliny and Virgil that may have provided North further inspiration are as follows:

|

Next will I discourse of Heaven's gift, the honey from the skies. [Georgics, 197] |

|

two seasons are there for the harvest—first, so soon as Taygete the Pleiad has shown her comely face to the earth... [Georgics, 213] |

|

For after the rising of each star, but particularly the principal stars, or of a rainbow, if rain does not follow but the dew is warmed by the rays of the sun, not honey but drugs are produced, heavenly gifts for the eyes, for ulcers and for the internal organs. And if this substance is kept when the dogstar is rising, and if, as often happens, the rise of Venus or Jupiter or Mercury falls on the same day, its sweetness and potency for recalling mortals' ills from death is equal to that of the nectar of the gods. Honey is obtained more copiously at full moon, and of thicker substance in fine weather. [Pliny, 455] |

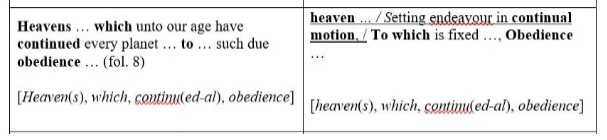

The first comparison relies on the words Heavens / heaven, continued / continual and obedience. In North the text from which these words are extracted has nothing in particular to do with bees. He is stating a commonplace of the time that the heavens (stars, planets, etc.) obey the god who created them. Writing a text against rebellion, as he was, obedience could only be highlighted from a story about the orderly commonwealth of the bees.

Heaven does not refer to planets, stars, etc., in the Shakespeare quote. The word is a metonym designating god.

As for the use both North and Shakespeare make of the word obedience we need to place the word in its context in each passage..

|

Bees have their special leader, whom they so much honor, as they will no day depart the hive before they have presented duty and saluted him... [the obedience of bees (in margin)].

George North, Rebellion |

Therefore doth heaven divid The state of man in divers functions, Setting endeavor in continual motion; To which is fixed, as an aim or butt, Obedience: for so work the honey-bees, Creatures that by a rule in nature teach The act of order to a peopled kingdom.

Shakespeare, Henry V, I.ii. |

In Shakespeare, the quote states the division of labor among the bees has obedience as its aim. The quote refers directly to Georgics IV:

|

For some watch over the gathering of food, and under fixed covenant labour in the fields; some, within the confines of their homes, lay down the narcissus' tears and gluey gum from tree-bark as the first foundation of the comb, then hang aloft clinging wax; others lead out the full-grown young, the nation's hope; others pack purest honey, and swell the cells with liquid nectar. Etc. Georgics, 207. |

Finally, the ancient Romans did not a have a parliament but rather a senate. Tudor England did not have a senate but rather a parliament. Thus North alone translates senate as “Parliament”.4

|

...they have a government and individual enterprises and collective leaders,... [Pliny, 439] |

|

…the crowd of older bees, who form a kind of senate [senatus],... [Columella, 469] |

Again, North seems clearly to have these texts beside him. This particular would seem to show that they also included not only Pliny but Columella's De Res Rustica.5 Shakespeare, on the other hand, is working from memory and mostly recalls the Pliny, however much more vaguely, and the Columella not at all.

1 Pliny the Elder. Natural History (1967). dual language tr. H. Rackham. Book XI. 432-499. Citations are by page number.

2 Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro). Eclogues, Georgics, Aeneid I-VI (1938). dual language tr. Fairclough, H. Rushton. Georgics IV. 196-237. Citations are by page number.

3 onera = burdens

4 Curiously, Edward de Vere's secretary, John Lyly, also translates senatus as “Parliament” in his description of the commonwealth of bees in his Euphues, his England (1580). See Arber edition, 263. “[The bees] call a Parliament, wher-in they consult, for lawes, satutes, penalties, chusing officers, and creating their king,”

5 Columella, Lucius Junius Moderatus. On Agriculture III. De Res Rustica V-IX (1954). dual language tr. Heffner, Edward H. 468-9.

Also at Virtual Grub Street:

- Rocco Bonetti's Blackfriars Fencing School and Lord Hunsdon's Water Pipe. August 12, 2023. “... the tenement late in the tenure of John Lyllie gentleman & nowe in the tenure of the said Rocho Bonetti...”

On Shakespeare's lameness and historical-fiction biography, etc. August 5, 2023. “Those who support Sogliardo of Stratford and other authorship candidates generally stop by from time to time to remark...”

- Shakespeare CSI: Sir Thomas More, Hand-D. April 22, 2023. “What a glory to have an actual hand-written manuscript from the greatest English writer of all time!”

- Robert Greene and the Construction Shakespeare Never Used. August 9, 2022. 'Our first foray “staring intently into” the texts of Robert Greene has noted that his work utilized far fewer feminine endings than Shakespeare’s.'

A 1572 Oxford Letter and the Player’s Speech in Hamlet. August 11, 2020. “The player’s speech has been a source of consternation among Shakespeare scholars for above 200 years. Why was Aeneas’ tale chosen as the subject?”

- Check out the Shakespeare Authorship Article Index for many more articles and reviews about this fascinating time and about the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

- Check out the Letters Index: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford for many letters from this fascinating time, some related to the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

No comments:

Post a Comment