- Shakespeare and Thomas North

- The Thomas North Theory Springs Leaks Under Scrutiny.

- More on Thomas North as Shakespeare and author of Arden of Feversham.

- On Claim that Thomas North wrote Arden of Faversham in 1550s.

“The most common reason,” I went on,

that software analysis has arrived at incorrect and/or pre-ordained outcomes is that neither the developers nor the users know much of anything about Tudor times or literature.

Sadly, that would clearly seem to be the case with the

Thomas North as proto-Shakespeare theory of Dennis McCarthy and June Schlueter.

Looked at closely, key items of evidence simply crumble to dust. And for

reasons that leave the entire theory in question.

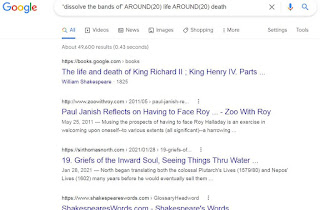

For all I thanked Mr. McCarthy for bringing to my attention the “AROUND (X)” Google Search function, I must bring to his attention a raft of search engine challenges in exploring Medieval and Tudor texts on the Internet. In McCarthy’s video “How We Know Sir Thomas North Wrote Richard II,” at 1:10, we are informed that “there is zero doubt that this was the passage used.”

The passage to which he compares “He would… dissolve the

bands of this life,” from North’s Nepos Lives (1602), is this from Richard

II, II.ii.70-2:

A parasite, a keeper-back of death,

Who gently would dissolve the bands of

life,

Which false hope lingers in extremity.

Or, at least, it is similar to the passage in Richard

II, for all it is not the same. McCarthy searches on ‘“dissolve the bands

of” AROUND(20) life AROUND(20) death’. But the original passage in the 1st

Quarto of 1597 actually reads:

A paraſite. a keeper

backe of Death,

who gently would

dissolue the bands of life,

VVhich False Hope lingers in extremitie.

Because he has put his search terms in quotes, Google will

only search for exactly the same spellings. This is only the most obvious

reason why his statement that the engine checked the text “on the more than 100

trillion web pages on Google or 40 million books on Google Books show[ing] no

results except for works quoting Richard II or North’s Nepos Lives” is deeply

flawed.

If he had searched on “dissolue” — which uses the dominant

Medieval and Tudor typographical representation for our modern V: “U” — in mere

minutes, on the EEBO search engine, he would have found a considerable number of close variants to his original Google query for ‘“dissolue the bands of” AROUND(20) life AROUND(20)

death’[1]:

beholding death to be at the gates of my bodie, come vnto

thee, by the vertue of a fruitfull faith; beseeching thee, when thou shalt see

it meete and conuenient, that he shall dissolue the bands of this vading life

It is taken from a 1582 florilegium collected by “Thomas

Bentley of Graies Inne” entitled The monument of matrones conteining seuen

seuerall lamps of virginitie, or distinct treatises. True the word “death”

is more than 20 words away but then the entire passage addresses death, and,

furthermore, McCarthy has yet to cite the studies that inform him that “AROUND(20)”

yields irrefutable results as he so vigorously asserts.

The misery of having to backdate endless Tudor-ized

combinations upon modernized search phrases with the word dissolve,

numerous times in numerous combinations, using dissolue, disolue, dessolue, desolue

is, sadly, a requirement of computerized searching in electronic texts. Then

there is the matter of life, lyfe, lyf, death, deth, dethe, and of band,

bande, baund, baunde, and even bond, bonde, etc. And it is necessary to try the

variations with every combination of search quotation marks (including none). All possible

combinations must be checked before one can feel tentatively… um… confident.

My experience is that it is absolute drudgery. Welcome to

the team.

Google search engine, by the bye, does not check across

anywhere near 100 trillion pages when you enter in a word or phrase to search. As

a rhetorical trope, it gets across the idea of the vast range of search I

suppose. The vast majority of the pages of the Internet are never or rarely

“crawled” by a search crawler. As for the 40 million books, the search is so

spotty nowadays, with the greatly reduced support Google gives the platform,

that it is even less dependable than it was during the 2014 to 2018 golden age.

Even then, the seeker needed to know an impressive range of tricks to force

Google Book Search to acknowledge the presence of any texts that weren’t

regularly visited or that it just wasn’t in the mood to acknowledge.

That said, McCarthy’s idea of using of search engines is pointed

in all the right directions. He just needs

to learn a lot more about Tudor context and absolutely maddening search engine

perversity.

It only takes until the 2:40 mark of the video to be

informed that only North’s Dial could be the possible source of a number

of phrases including the precise five words “Oh, What pity is it”. Spell pity

the old fashion way(s), however, and suddenly it is everywhere. A translation

from A dispraise of the life of a courtier, and a commendacion of the life

of the labouryng man (1548) by the highly popular author Antonio de Guevara

is just one of many matches and close matches.

O what pitie is it to se a poore suiter in his nedy busynes

folowe the kyng from toune to toune euil norished ...

Also popular was Thomas Lodge in whose A margarite of America

(1596) we find the following:

O what pittie is it thou peruerse man, to see how I haue

bought thee of the gods with sighes

I give only two examples among many.

Some number of readers, here, will recognize Lodge was a

one-time secretary to Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. But

this is not why Shakespeare used “O, What pity is it” in Richard II. He

used it because the phrase was a commonplace in the 16th

century. As were variations upon the phrase “dissolve the bands of”.

The first and absolutely essential rule of Tudor-ized

computer search, you see, is to have read many hundreds of thousands of pages

of Tudor literature. When possible choose to read it in the original irregular

spelling. This is what McCarthy’s searches for his North theory would seem to

lack almost entirely.

More to come. Unfortunately, mooch more.

[1]

McCarthy does show the spelling “dissolue” in his ProQuest search of EEBO but

it didn’t offer the necessary search flexibility and he didn’t set the search parameters

properly. Had he only left the “PRE” function in its default setting, and read

the full passage that would have come up, he would have seen at least one potential

exception to his statement. The better choice is to use the EEBO Search without

quotation marks and to actually read the resulting passages.

Also at Virtual Grub Street:

- Shakespeare and Thomas North. April 5, 2021. “It might have been more of a surprise if North had not been advanced after one or another fashion.”

- On Shakespeare and Drinking Smoke. January 4, 2021. “The debate raged for some time: Had Shakespeare smoked pot? Tobacco? Both?”

- On the Question “Who knew Edward de Vere was Shakespeare?” December 14, 2020. “But was the word going around that his wife, the Countess of Oxford, conceived two children in his absence?”

- A 1572 Oxford Letter and the Player’s Speech in Hamlet. August 11, 2020. “The player’s speech has been a source of consternation among Shakespeare scholars for above 200 years. Why was Aeneas’ tale chosen as the subject?”

- Check out the English Renaissance Article Index for many more articles and reviews about this fascinating time and about the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

- Check out the Letters Index: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford for many letters from this fascinating time, some related to the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

1 comment:

Purdy only highlights three lines. Actually, the full North/Shakespeare borrowing extends for dozens of lines -- in which both are describing griefs of the inward soul and marking it as a loss of perspective. He is simply examining to see if one of the borrowed elements is unique in the history of literature--and the only other passage that he finds in history is a little known prayer referring to "this fading life," but that passage has nothing to do with grief and has none of the other shared elements. More, I appointed out this little known prayer in my post on the subject: https://wp.me/pck4h5-o5

Post a Comment